Four hundred years after its destruction, the temple extolled by the ancient Tamil saints rises once again in ornate granite

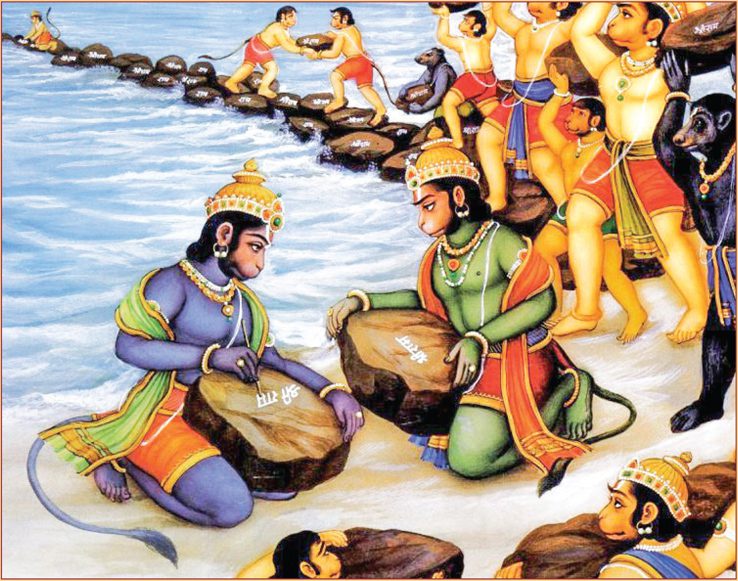

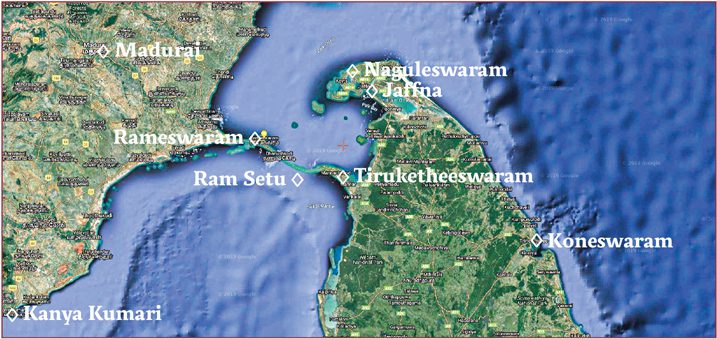

FEW HINDU TEMPLES ARE AS TIED INTO HINDU religious history as Tiruketheeswaram. It is named after the planetary being Ketu, who performed penance here for stealing the Gods’ amrita, the nectar of immortality produced during Samudra Mantham, the churning of the ocean. Ram Setu, the land bridge connecting India and Lanka, built by Lord Rama’s army of monkeys to rescue Sita from Ravana, reaches Lanka at this point. And, aptly for our story, this place is associated with Vishwakarma, the Divine Architect responsible for all construction—from houses, cities and forts to the great temples throughout India and Lanka. His tradition lives on today in the sthapatis (master builders) and silpis (artisans) responsible for erecting and repairing the holy shrines. Though its historicity and sanctity are undisputed, Tiruketheeswaram Temple was totally obliterated by the Portuguese in 1589. Even its location was all but forgotten until the advent of Arumuga Navalar in the 19th century. Join our reporter, Anuradha Goyal, as she visits this ancient place and reports on the efforts to rebuild the great temple.

BY ANURADHA GOYAL

REPORTING FROM MANNAR, SRI LANKA

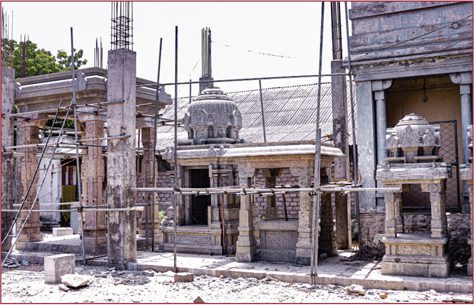

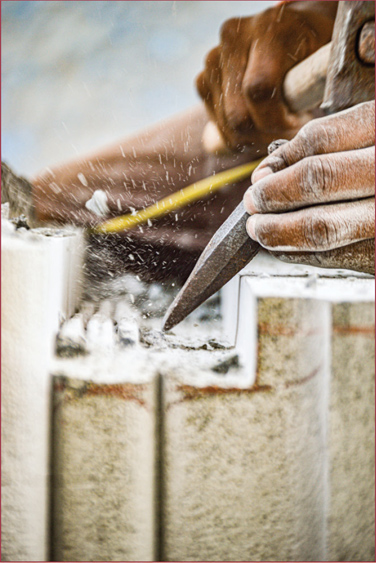

On an early morning in June 2019, I am at the Sri Tiruketheeswaram Temple at Mannar in Sri Lanka, very close to the southern end of Ram Setu, which joins Rameshwaram in India to Sri Lanka. A team of silpis, who have been brought here from nearby Tamil Nadu, India’s southernmost state, are sculpting the hard granite stone in various hues of grey. One uses a hammer with a spiked metallic pattern to give the machine-cut stone a matte finish. Another uses a similarly fashioned flat-headed chisel, tapping it with a small mallet to smooth the rough stone into the finish that will endure for centuries to come. Other artisans are using small or large electric grinders to cut the granite, while still others are chipping off bits of stone with hammer and chisel. All work in harmony to fulfill the designs laid out by Selvanathan Sthapati, the temple’s chief architect who flies here from India to oversee the project.

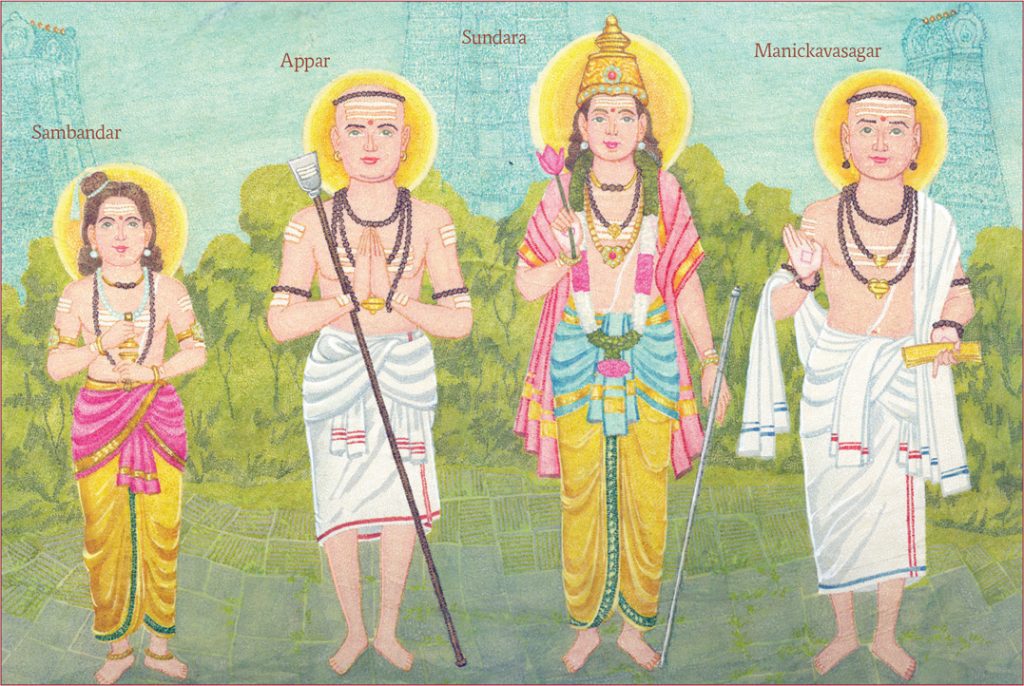

Tiruketheeswaram is one of the five ancient Iswarams, or great Siva temples, along the shores of Sri Lanka: Naguleswaram on the north coast, Koneswaram on the east coast, Thondeswaram in the south, Munneswaram on the west coast and here, Ketheeswaram, also on the western coast toward Jaffna. These five ancient temples were all demolished by Portuguese soldiers when they conquered the island in the 16th century. All of them except Thondeswaram have been rebuilt by the devout Hindus of Sri Lanka. The very location of Tiruketheeswaram was lost; its rediscovery in 1894 was the result of intense efforts by the Jaffna Tamil community to find and resurrect it. Helpful in this effort were the songs of the early Tamil saints, including Sambandar and Sundarar, whose images now adorn two of the temple’s eight new pillars leading to the main sanctum. Thondeswaram, similarly lost, is thought to have been located in the Galle area at the southern tip of Sri Lanka. But little more is known.

The Tamil Hindu community began serious efforts to reconstruct Tiruketheeswaram in the early 1900s. Recently, the Indian government has generously contributed to the project, supplying funds and expertise to replace several key parts with granite stone (much preferred over concrete). India is uniquely endowed with the knowledge and skills to build Hindu temples, and this project is one that is dear to Sri Lanka’s three million Hindus. But before we describe the current project, let us go back in history to the origins of this sacred place.

In Scripture and Historical Record

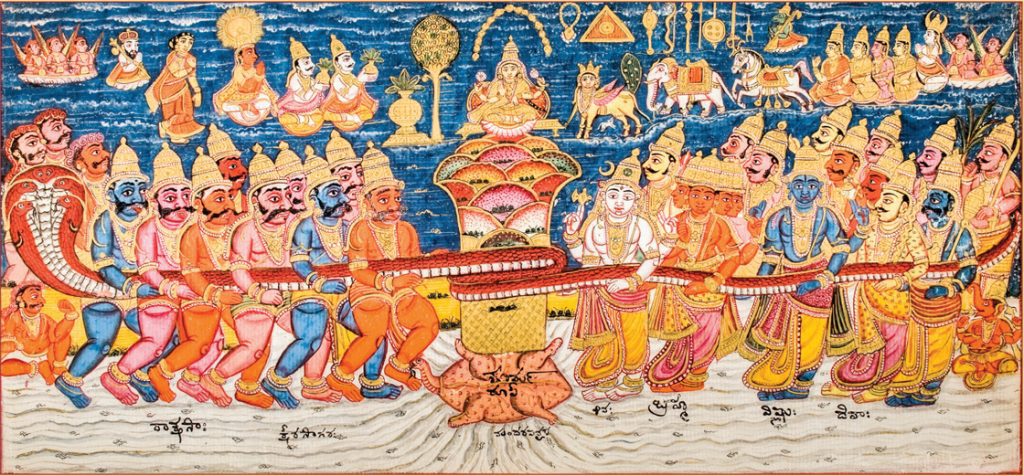

The temple’s scriptural origins trace back to the story of the Samudra Manthan, the Churning of the Ocean, which is recounted in the Bhagavat Purana and the Vishnu Purana as well as the Mahabharata. Among the many treasures yielded by the churning, the most prized is amrita, the nectar of immortality, which was claimed by the devas after a victorious battle with the asuras. But during the nectar’s distribution, some was surreptitiously consumed by an asura named Rahuketu.

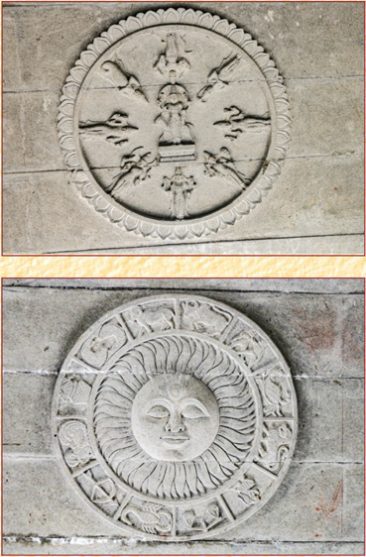

He was caught in the act, and the Goddess Mohini cut off his head with the Sudarshana Chakra. Rahuketu remained immortal, but in two pieces. His head was called Rahu and the serpent-like body was named Ketu. In Hindu astrology, these two beings are the north and south lunar nodes—the points where the Moon’s orbital path crosses the apparent path of the Sun against the sky, a time when eclipses can occur. Ketu resolved to perform penance for stealing the amrita, and chose to do so eight miles north of Mannar city. Lord Siva was pleased with Ketu’s severe austerity. In commemoration, the place was named Tiruketheeswaram, “the holy place where Ketu worshiped Siva”—just as Rameshwaram, the temple on India’s southern shores, means “where Rama worshiped Siva.”

The area of Mannar, or Mathoddam as it was once known, is also said to be the land of Vishwakarma, the Divine Architect, whose five sons were the progenitors of five artisan clans—Manu for blacksmiths, Maya or Mayan for wood craft, Twashta for metal craft, Silpi for stone craft and Viswajna for goldsmiths.

Nala Setu, Lord Rama’s engineer for the monkey-built Ram Setu land bridge to Sri Lanka, was a descendant of Vishwakarma. Selvanathan Sthapati, Tiruketeeswaram’s chief architect, also traces his ancestry to this place. He shared with me that working on this project has been a great fulfillment of his life.

Mandodari, the chief queen of Ravana in the epic Ramayana, is thought to be the daughter of Mayan, who lived in Mannar and built Ravana’s golden capital, Lankapuri. Sculptures of Mandodari can be seen at many places in the rebuilt Tiruketeeswaram Temple, including on one of the entrance tower pillars. The Ramayana relates that she prevented Ravana from killing Sita for refusing to marry him.

Mannar is traditionally associated with the serpent-worshiping Naga people, thought to be an aboriginal tribe of Lanka that was eventually absorbed into Tamil society. Serpent symbols are seen everywhere in the region. In the temples many Deities are shown standing or sitting under a cobra hood (see photo of Ketu on page 28). Historically, most Sri Lankan kings married Naga princesses from this area.

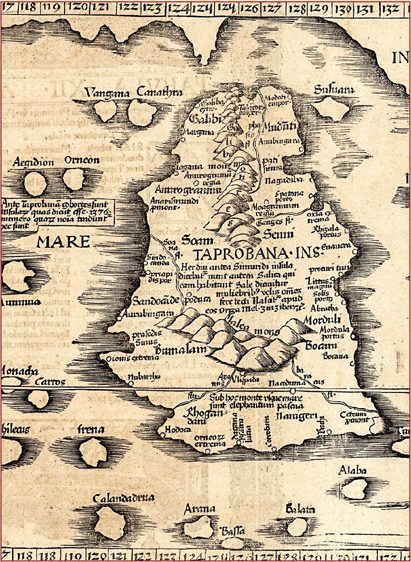

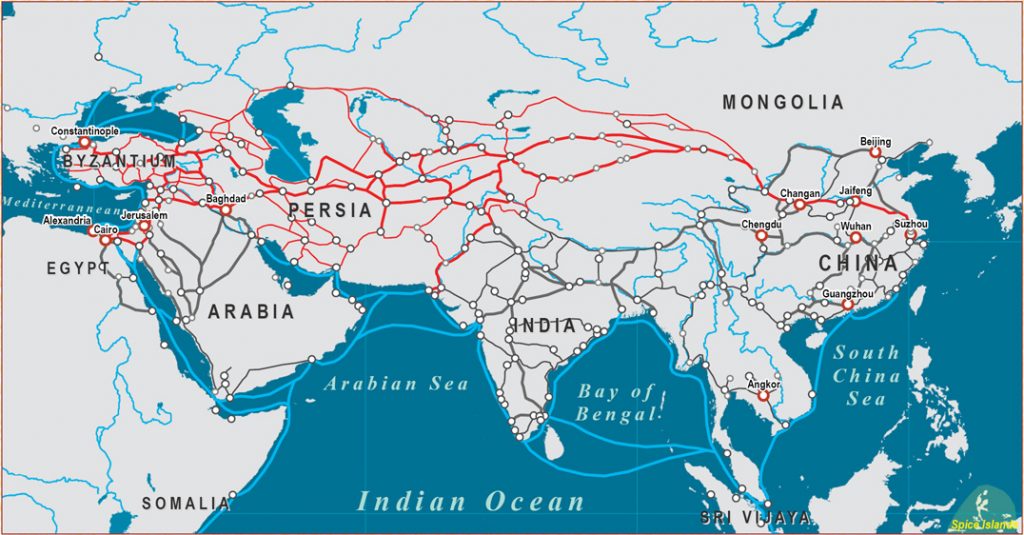

Mannar was Lanka’s main sea port until relatively recent times, frequented by Chinese traders from the east and the Greeks and Romans from the west. Ptolemey’s first-century map of Sri Lanka, then called Taprobana, shows Mannar as Margana to the north on the western coast. This was a natural trading center, due to its location at one end of Ram Setu (called “Adam’s Bridge” by tenth-century Muslims). Ships coming from east or west could not proceed past Ram Setu. Sailing completely around Sri Lanka was possible but impractical. Half the year, the wind took ships in one direction, the other half in reverse, meaning ships might have to wait precious months for the wind to change. Until the development of modern navigation methods, it was far more practical for ships from China and other eastern ports to unload at Mannar and trade there for goods coming from Europe, the Middle East and western India. It became a central marketplace for international trade for many centuries.

Ancient Trading Routes

Temple records in South India indicate that until 1480, when a massive cyclone broke it apart, one could cross Ram Setu on foot. Between such land travel and the abundant fishing fleets, it was easy for pilgrims to reach Lanka. Thus it is not surprising that the earliest written records of Tiruketheeswaram are found in the songs of the Tamil saints, starting with Tirunavukkarasar (Appar), who lived during the reign of the Pallava king Mahendra Varman I (580-630). Appar mentions the temple in his song, Tiruthandakam: “The holy ash shines on His golden hue. He wears the sacred thread. The fiery serpent adorns His form. He is our Lord, Shankar by name. He dwells in Keteeswaram there, He of Ketharam and Veeraddanam in the North.” (Ketharam is modern Kedarnath in the Himalayas; Veeraddanam is the Tiruveeraddanam Siva Temple in the Kadalur District of Tamil Nadu.)

Seventh-century saint Tirugnana Sambandar from Seerkali in Tamil Nadu sang of the glories of the Lord of Tiruketheeswaram in eleven of his devotional Thevaram songs (youtu.be/_rYeie9DvzI): “Our Lord loves this shrine for the sake of His devout worshipers, worshiping in love and truth. He has taken residence at Tiruketheeswaram for the sake of devas who seek spiritual comradeship with Him. Worshipers at Tiruketheeswaram are immensely blessed. They are liberated from the law of karmic effect and bestowed with supreme wisdom and bliss.”

The eighth-century poet Sundarar sang ten songs about this temple (youtu.be/tDGdYqY5L-k). In one, he mentions its sacred tank Palavi, the abundance of pearls in the sea and the busy port: “Hail! O Lord of Tiruketheeswaram! Hail to You, O Lord, who presides with the beautiful consort Umadevi, on the celebrated banks of Palavi at Mannar, by the sea which abounds with pearls.”

Mannar repeatedly finds mention as a vital port in various chronicles from the early centuries ce. It was known by various names in addition to Mathoddam—Thuvadda, Mahathuvadda, Mattodai and Mahatitta. Keerimalai, north of Jaffna, was the main city and Mannar was the primary port.

The South Indian kingdoms dominated Sri Lanka for much of this period, which was also the golden age of temple architecture. The temple was improved upon and expanded by various rulers, including the Cholas and Pandyas. A mid-13th century inscription at Chidambaram Temple in South India describes the rebuilding of Tiruketheeswaram Temple in Pandyan style.

Mannar remained Sri Lanka’s main port until the 16th century, when the Portuguese developed Colombo’s natural harbor, which had been used for shipping on a small scale from ancient times. Mannar’s prominence also diminished as navigation methods improved and ships no longer needed to sail within sight of land. Mannar’s periodic pummeling by severe cyclones, such as the one that breached Ram Setu, was probably another factor in its decline.

The port town is today something of a buried treasure. Storms occasionally reveal coins, beads and other artifacts from the time of abundant trade with Arabs, Persians, Romans, Greeks, Indians in the west and with Chinese, Javanese and Burmese in the east. The cosmopolitan nature of the port must have been like that of Puhar in South India, described in the early Tamil poem, The Ankle Bracelet, or like that of Florence during the European renaissance.

The arrival

of the Portuguese in 1505 spelled complete disaster for not only Tiruketheeswaram, but nearly all of Sri Lanka’s Hindu temples. These archeological and religious treasures were systematically destroyed and their building materials reused for forts and churches. The story of the blowing up of Koneshwara Temple is well known; Tiruketheeswaram Temple met with a similar fate, though the details are lost to history. The last known puja in the temple was in 1589; its total destruction was recorded in 1590. British records chronicle that the temple was as big and as revered as the one in Rameshwaram across Ram Setu. It boasted seven prakarams, successively larger enclosure walls, with three moats and multiple gopurams and shrines. Pilgrims from all over India used to visit.

Developing the Outer Courtyard

After the Portuguese came the Dutch, who by 1660 gained control of all of Lanka except Kandy. In what Hindus might call karmic justice, the Protestant Dutch persecuted the Catholic Portuguese but left Hindus and others mostly alone. For example, Jaffna’s Nallur Temple, destroyed in 1624 by the Portuese, was rebuilt by the Hindu community in 1734 during Dutch rule. Then, in 1815, the British gained complete control of Lanka. They took a hands-off approach to religious issues. All during occupation, Hinduism and its temples remained active but subdued.

Lanka’s Hindu Renaissance

In the mid-19th century a young man from Jaffna, Arumuga Navalar (1822–1879), studied Saiva Siddhanta philosophy, bought a printing press and started publishing books on Hinduism. His main focus was to bring back the worship of the Sivalingam and the singing of the Tamil holy hymns, Tevaram and Tiruvasagam, in temples. He regaled saints Sambandar and Sundarar, who described the Lord of Tiruketheeswaram, and became determined to rebuild the original temple. Its location in Mannar—today a small and remote fishing hamlet—was known to be in an overgrown jungle area.

Arumugam passed away in 1879, but by then he had built up a movement that his extended family and followers carried on with great zeal. In 1889, 400 years after the Portuguese destruction in 1589, they started the process of acquiring from the British government 44 acres of land where a large but damaged Sivalingam from the Chola period, a Nandi statue, a Ganesh statue and a Somaskanda in bronze had been unearthed. These treasures can be seen on the grounds today. Coins, jewelry, beads and gemstones have also been unearthed.

On June 27, 1903, a shrine was consecrated on the land, with a new Sivalingam called Kriya Lingam and an image of the Goddess Gowri, brought from Kashi via Rameswaram. Because of its damaged state, the old Sivalingam could not be reinstalled in the central sanctum, so it was kept to one side and worshiped regularly as “Mahalingam.” During the following seven years, a small temple was built around the main Deities. A kumbhabhishekam was performed in June, 1910—109 years prior to my visit. The local Nagarathar community was handed the responsibility to run temple activities and initially to perform the worship. Traditional brahmin priests were hired later to perform the puja worship.

In 1948, the Tiruketheeswaram Temple Restoration Society (TTRS) was formally established. Its first president was Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan (1896-1965) of Kopay, a respected civil servant and politician. One of the group’s first accomplishments was the 1949 revival of Palavi Teertham, the temple water reservoir. A huge festival was held in which, after a lapse of 400 years, the ritual of taking the Deity to the water, about 200 meters south of the temple, was resumed. The large lake is surrounded by green trees and hosts many birds. A second, smaller tank is located in front of the temple near the goshala (cow shelter).

In the 1950s the TTRS set the ambitious task of rebuilding the entire temple. They hired two sthapatis, traditional temple architects, from Karaikudi—M. Sellakannu Sthapati and his brother M. Vaidyanatha Sthapati—Selvanathan Sthapati’s grandfather. Plans were drawn to expand the temple adding a prakaram or enclosing wall to contain smaller shrines within this outer area. Granite stone was acquired from Vavuniya, about 50 miles inland from Mannar. The foundation for these improvements was laid in 1953. Many parts were built in concrete.

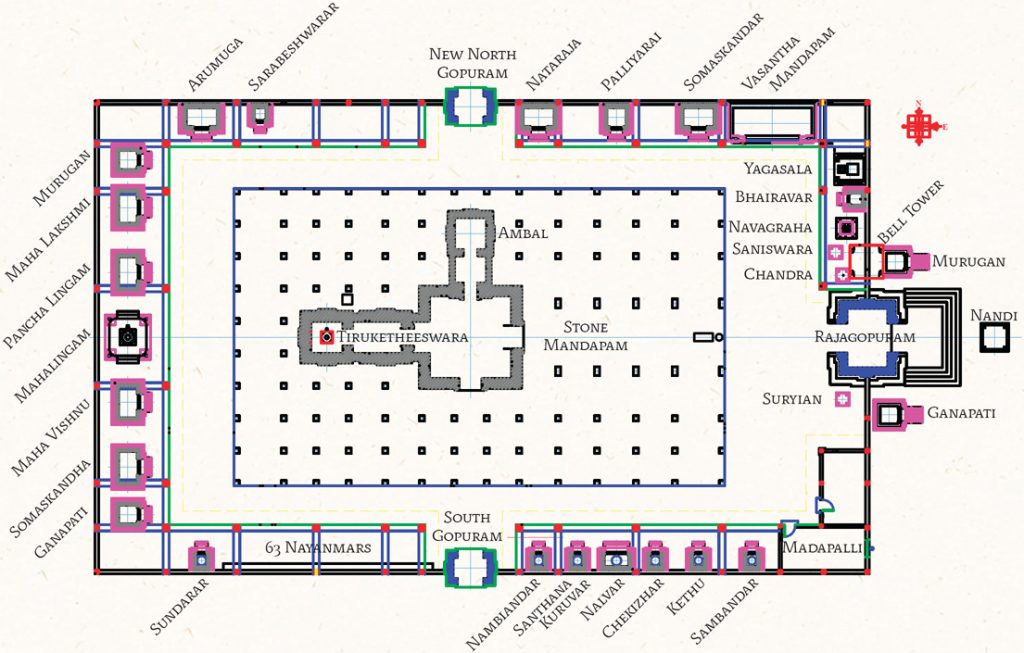

New shrines were erected for the Goddess, worshiped here as Gowri Ambal; Nataraja, the dancing form of Siva; Dakshinamurti, Siva as the silent teacher; Skanda, Vishnu and others along with the 63 Tamil Saiva saints, Nayanmars, and the divine being Ketu, who founded the temple. These new shrines were dedicated in 1960.

The following year a large temple bell imported from England was installed in a tower at the front entrance. A tower with a European bell has been a unique feature of Sri Lankan temples ever since one was installed at Nallur Temple, the first temple rebuilt after the end of Portuguese rule. The priest here tells us they are easy to ring and can be heard from a long distance.

A gurukulam (priest training school) opened in 1962, offering a five-year program. Six years later a five-tiered raja gopuram (entry tower) was built at the main entrance. Reconstruction of the primary shrines for Siva and the Goddess began in 1971; these were dedicated in 1976. Marriage facilities boosted the temple’s popularity, and last rites were regularly performed at Palavi Tank.

Rest houses were built nearby to host pilgrims from Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia and other countries. Most of those coming from India took the ferry that then operated between Rameshwaram and Mannar, a voyage of 46 miles. Some flew from Tiruchirappalli in Tamil Nadu to Jaffna. In the early 1980s, TTRS planned to rebuild the covered area around the central sanctum with stone pillars and create a larger entry tower. But history intervened.

War Intervenes

With the 1983 outbreak of civil war between aggrieved Tamils and the Sri Lankan government, all plans for the temple were put on hold. The Sri Lanka army soon secured Mannar, along with other coastal areas in the north that were subject to infiltration from India. By 1990 people living around the temple moved to less restricted areas, and eventually even the priests and their families fled. The army secured the temple in 1990 and did not allow priests or devotees access again until 2002. Though not deliberately damaged, the temple was deserted.

Mrs. Abhirami Kailasapillai, the joint secretary of TTRS, affirms that the army was respectful of the temple. They would light a lamp and not step inside with shoes on. However, neglect took a terrible toll on the temple. As many as 20 of the 27 pilgrim rest houses were damaged or lost. When the TTRS revisited the temple in 2003, the army was still in control and they had to pass through many checkpoints before entering. Even the windows of the bus they traveled in were papered over, according to local news reports. This situation continued until 2009. Several permissions were required to visit the temple, no private vehicles were allowed and every activity required advance permission from the army.

With the war’s end in May 2009, Mrs. Kailasapillai, president of the All-Ceylon Hindu Congress, and others could once again travel freely to the temple, which by then had become enveloped in tall grass and shrubs. Signs of the war were everywhere, but the temple itself was intact. It was finally time, they felt, to bring it back to life. A small reconsecration was performed, and daily pujas resumed. The following year devotees regained free access, and the construction projects abandoned in the 1980s could be started anew, this time with assistance from India.

Bringing Beauty from Granite and Concrete

Reconstruction Resumes

In June 2010 India and Sri Lanka issued a Joint Declaration laying out numerous policies and projects to address the reconstruction of northern Sri Lanka following nearly three decades of war. In addition to generous amounts of humanitarian aid and major infrastructure repair, one item specifically called for the restoration of Tiruketheeswaram Temple. The Archaeological Survey of India and the College of Architecture and Sculpture at Mamallapuram would coordinate with the Department of Archeology of Sri Lanka. In 2011 a formal MoU was signed between the two governments and TTRS. Financial aid to the tune of us$3.2 million was provided to cover both labor and material. The dual-nation effort was launched in August 2012 by Kumari Seilija, then India’s minister for culture.

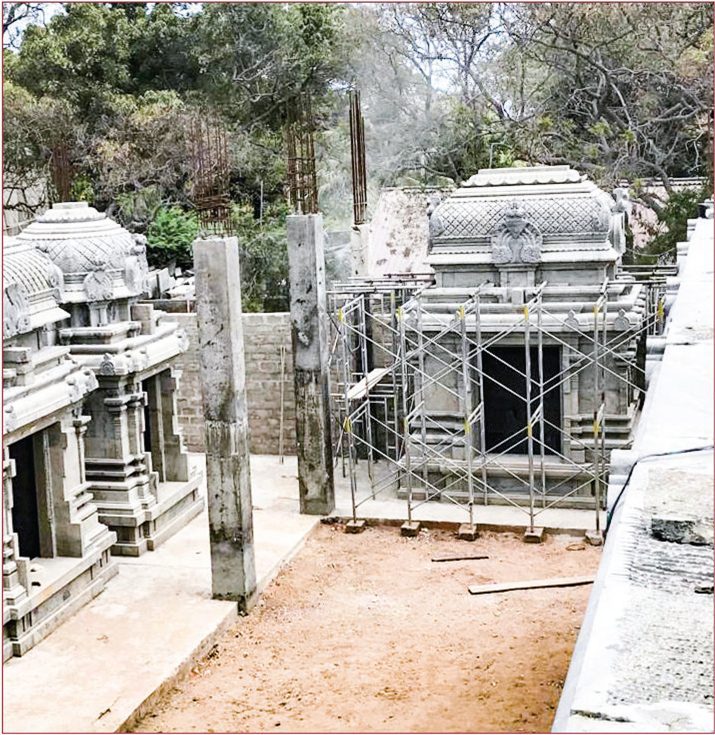

The plan called for three structures: the mahamandapam (the area around the central sanctum), the prakara mandapam or inner courtyard area, and the vasanth mandapam where the parade Deities are kept—a total area of 11,370 square feet. The existing mahamandapam, made of concrete, was to be demolished and rebuilt in granite. A hundred pillars, carved at the Government College under Dr. V. Ganapati Sthapati’s guidance in the late 1980s, were shipped along with other stones to Sri Lanka. Dr. M. Gunasegaran, his successor at the college, oversaw their installation. They included six huge pillars, which are now positioned in front of the main sanctum, carved with life-size statues of King Rajaraja Chola, his son Rajendran Chola, Mandodari, Kethu, Sambandar and Sundarar. Dr. Gunasegaran retired from the college while the work was still in progress, but TTRS continued to engage him with oversight by the Archeological Society of India. This first stage of this restoration plan was funded by India and completed in 2017; subsequent work has been funded by TTRS from investments and donations.

The second stage for the temple includes reconstructing the vimanas, elaborate towers, over the main Siva and Gowri Ambal sanctums and the surrounding 24 subsidiary shrines, sannithis, all in stone. This will bring about a uniformity in architecture and design to match the Mahamandapam, which was completed in stage one.

According to Mrs. Kailasapillai, funds raised prior to and during the civil war were invested in stocks, the proceeds of which are today a major financial strength for the restoration. At the same time, she said, there are major challenges in terms of paperwork and permissions required for the project.

The immediate goal of TTRS is to finish the ongoing restoration work and perform a kumbhabhishekam. Presently the central sanctum is closed, and worship is performed in the balalayam, a temporary chamber just outside the Rajagopuram. After the rededication, the premises will be returned to its previous use as a wedding hall, and the normal functions of six pujas a day and major festivals will be resumed.

The project has been fraught with challenges. In an unusual incident on Sivaratri day, 2019, a temple gateway spanning the road to the temple near a Catholic church was torn down. A YouTube video shows church parishioners, including several women, tearing down the sign while priests from the church look on. The Catholic Church in Jaffna apologized for the incident, which is now in the courts. But it was a reminder that Mannar is a Catholic majority area. Hindus are struggling to rebuild it and have had no relief from authorities in the area.

The Present Work

Visiting the temple today, we feel the timelessness of an ancient Siva temple and the steady pace of the remaining work: the kumbhabhishekam is scheduled for next year, and there is much yet to be done.

Sthapati R. Selvanathan of Chennai, India, one of the foremost traditional temple architects living today, has been retained by the temple to complete the project, which include the central prakaram (with 24 shrines) and vasanth mandapams. As already mentioned, Selvanathan is the nephew and disciple of Ganapati Sthapati, grandson of Vaithianathan and grand nephew of Sellakannu—the two architects first hired to rebuild the temple in the 1950s. Coming from the Sthapatya lineage, Selvanathan is proud to be associated with the temple that his guru also worked on.

Sthapati strongly believes that we must focus on restoring our existing temples in India and Sri Lanka instead of building new ones. He has worked on many such sites in India. Outside of India, he’s worked on many new temples around the world, including Iraivan Temple at Kauai’s Hindu Monastery, home of HINDUISM TODAY, which was originally designed by Ganapati Sthapati.

Selvanathan explains that there are four types of temple restoration or jeernodhar, as laid out in the Silpa Shastras. First is the regular maintenance done every 12 years to rejuvenate, renew and expand the temple. Second is renovating or restoring of an abandoned temple after it has stopped pujas. Third is building a new temple. The fourth is rejuvenating or re-energizing the temple’s divine vibrations following natural or man-made disturbances, such as tsunamis, earthquakes or war. In each case the extensive ceremonies of kumbhabhishekam are performed.

Attention to Detail Guides the Project at Every Turn

Forty silpis from India are working at the Mannar site. Local Sri Lankans help, but there is no guild of silpi carvers in this small nation. All around the temple, stones are being cut, dressed and sculpted to form the shrines lining the courtyard wall. The finished capstones for these shrines are ready to lift into place. A sense of the action can be seen in this recent YouTube video: youtu.be/oZ55l-hbt7c.

Ponni, wife of Sthapati Selvanathan, proudly recalls what Dr. V. Ganapati Sthapati used to say—the temple is not the home of the God, it is the form of the God. With that intent, they sculpt every stone as if they are composing the body of God Himself. Selvanathan explains the importance of measurement in the repair and renovation of a temple and how the temple must expand in proportion to a specific base unit. He quotes a Sanskrit verse that means, “If the measure goes down, the pride goes down; if the measure goes up, it hurts the patron.” The measurements have to be perfect for the energy to vibrate in a way that is beneficial for everyone.

The walls of the temple office are plastered with architectural drawings and the artistic impressions of how the temple will look. Sthapati is preserving the Pandiyan and Chola stylistic elements which play such an important part in the legacy of the temple. We are witnessing the conceptions on paper taking shape in stone.

Outside is the granite that has been sourced from nearby Vavuniya. The quality of the stone is judged by the “note” it sounds when struck with a hammer. The intended form, Selvanathan explains, is already present inside the stone; the silpis need only chip off the unneeded parts to reveal it. A prized work is the three-tiered capstone, vimana, of the Siva and Ambal sanctums that is replacing the earlier brick and mortar one.

The most precious artifact here is the Mahalingam, dated to the Chola period and regarded as the site’s Adi Dev or first Deity. When discovered during excavations in the area, it showed slight damage on the bottom. As well, the base in which it would have been set was missing. A damaged Deity cannot be reinstalled in the central sanctum, hence a new Lingam was commissioned for the 1910 reconstruction work. The Mahalingam, now set in a new base behind the central sanctum, remains a holy and highly regarded connection with the past. Pilgrims treasure the opportunity to personally pour water over the ancient form, something only the priests can do for the Lingam in the central sanctum. Given the icon’s popularity with devotees, the TTRS decided to build a small shrine with ornate pillars around it. During our visit, we have the opportunity to watch the silpis working on the stones for this shrine.

Current Status

The plan of the temple takes the visiting devotee first to the Chola-period Nandi, recovered during excavation and installed outside the Raja Gopuram. Then visitors proceed to the Ganesha shrines enclosing two ancient murtis discovered during the excavation of the old temple plus a new one carved on site.

For the demanding schedule of worship, the temple employs three priests. Thyagaraja Iyer Karunanda Kurukal, 46, is the chief priest. His father, Sri Panjachar Balasubramanya Gurukal Shivacharya, 72, handed over the position to his son upon the death of his wife, as a widower can no longer be a chief priest in the Sivachariyar tradition. Recently, Sivasri Somakalathara Kurukkal has joined the staff. All are of Sri Lankan origin.

Balasubramanya received his training in the nearby Sivananda Gurukula for Vedic Agamas. The school was a casualty of the war; the TTRS has plans to restart it, but for now, most priests are trained in India at private gurukulas. A major concern for him is that few youngsters are wanting to enter the priesthood today.

Balasubramanya recalls how he held on to the Sivalingas and refused to leave the temple during the civil unrest until he was confronted with a simple choice: stay and die or keep himself alive so that when the war ended, he could come back and restart the pujas. He chose to leave.

The round of rituals is done according to Karana Agama, following a typical schedule, with the first pujas at 4:30 am, again at 7:30, then noon, after which the doors are closed until 4 pm when it opens for late afternoon and evening pujas. A cow shelter on the premises supplies milk for the daily worship.

Balasubramanya explains that pilgrims come from all over Sri Lanka, especially during the annual Mahasivaratri festival. This festival is always well attended at Siva temples big and small, everywhere in the world. Here it is attended by half a million devotees from all across the island. They will first take a ceremonial bath in the Palavi tank, then carry a pitcher of water while circumambulating the Deities and finally perform abhishekam of the Mahalingam. The festival’s popularity is enhanced with lectures, concerts and Vedic chanting—all broadcast live on the radio.

The second most popular celebration here is the ten-day annual festival around the full-moon day in the month of Vaikasi (May/June). At other temples, each day of the festival is sponsored by a particular family, but here each day is sponsored by a particular school. The students will take up a collection, come by bus on their day, carry the Deity around the sanctum, cook food and participate in every aspect of the worship. Other major festivals include Navaratri, Ganesha Chaturthi and Skanda Shashthi.

The most devout few visit Tiruketheeswaram on a daily basis. There are buses every 30 minutes from Mannar, which in turn is well connected by road and rail to all major cities in Sri Lanka. Ceremonies here are best known to counter inauspicious astrology caused by Ketu, Rahu or Shani (Saturn). It’s also a popular place for weddings; in fact, we encounter a simple wedding ceremony in progress during our visit.

The story of Tiruketheeswaram Temple illustrates the adage that what goes down will come up again. The Nalvar’s poetry tells us of the temple as it existed a millennium ago, and colonial records chronicle its destruction 500 years ago. Recent history starts with its rediscovery 130 years ago, followed by its slow and steady reconstruction—temporarily halted by decades of civil unrest in the region, but now, at last, nearing completion. The holy consecration rites, kumbhabhishekam, are scheduled for 2020. With prayers, hard work and the blessings of God and the Gods, this sacred home of God Siva will once again reach the glory that inspires poetry.

The TTRS is far from finished with its work. Going forward, in addition to restarting the gurukulam, they plan to build four large gopurams around the temple so that it may be seen from afar.

Thiruketheeswaram temple:

phone: 023-205 0800

email: ttrsmannar@gmail.com

web: www.thiruketheeswaramtemple.org

Anuradha Goyal is one of India’s leading travel bloggers. Her key focus at www.IndiTales.com is ancient Indian civilization and temple architecture along with old techniques such as water management with step wells.

YouTube clandestinely removed the video [youtu.be/38L0FLbUKTc] of the Catholics’ attack on the Hindu temple at Mannar.

The same video can now be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uTrMykGhYX0. You may wish to replace the deleted link with the new link & update the article.